Date

August 1, 1946

Document

- View PDF (2 MB)

Description

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946, passed by the United States Congress in the summer of 1946 and signed by President Harry Truman on August 1, 1946, came after nearly a year of negotiation and drafts by Congress. An initial version of the law, the May-Johnson Act, was put forward with the blessing of the US Army, which also had a hand in the Act’s drafting. Congress, and eventually the President, rejected this bill as giving the military too much power over the control of the future of nuclear technology, an argument particularly pushed by the nascent Scientists’ Movement (see Hewlett and Anderson 1962, Smith 1965). The McMahon Act instead gained momentum. In its initial form, the McMahon Act represented the views of the Manhattan Project scientists with a strong focus on research and openness, although last-minute changes thwarted some of the scientists’ goals, including mandating heavy-handed punishments for the distribution of nuclear secrets. The overall framework of the bill nonetheless very much embodied the idea of “civilian control” of atomic energy, particularly given that the newly-created US Atomic Energy Commission, a civilian federal agency, would manage all aspects of the development of both military and peaceful nuclear technology.

Commentary

Citation

U.S. Congress, Senate, Atomic Energy Act of 1946, Public Law 585, S. 1717, 79th Congress, 2nd Session (1 August 1946).

Provenance

Gilman G. Udell, Atomic Energy Act of 1946 and Amendments (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1975).

Topics

Referenced in

Document entry started by Alex Wellerstein on May 31, 2018. Entry last updated by Mikael Kelly on October 15, 2018.

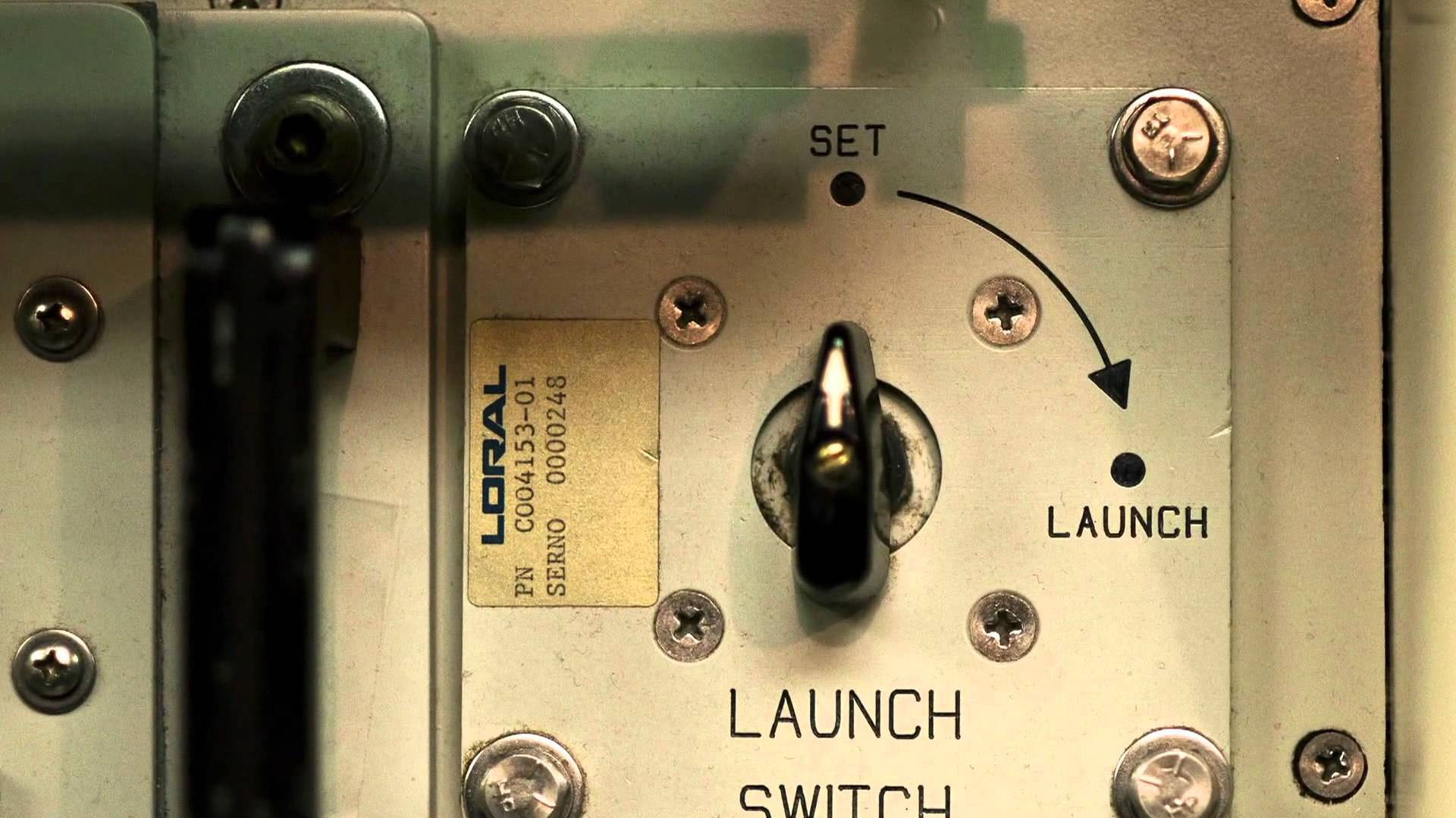

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 is often cited as the only formal statutory basis for Presidential nuclear launch authority. It does not, however, say anything about the use of nuclear weapons. It does give the President considerable power to determine policy about the manufacture of nuclear weapons, and, in a section titled “Military Applications of Atomic Energy,” it specifies that:

But this is about custody (who has physical access to the weapons), not use, which is an important distinction. Under the Truman administration, fear of premature military use of nuclear weapons meant that the AEC retained control over almost the entire stockpile. However, from the Eisenhower administration onward, the military obtained custody over nearly every weapon in the US stockpile. Despite having custody of the majority of the arsenal, the military was not allowed to use the weapons without Presidential authority, whether direct or delegated, which emphasizes the clear difference between custody and use.

The section of the Act pertaining to manufacture and custody was not substantially changed by the Atomic Energy Act of 1954.

While the Atomic Energy Act does formalize a general relationship between the civilian and military authorities, with the President as the authorized mediator, it does not formalize anything related to the use of the weapons.